Harry Thompson

Inducted into the NHTA Hall of Fame in 2000.

Native American Trapper:

Nestled along the south shore of the Missouri River in the state of South Dakota is the Lower Brule Indian Reservation, home of the Teton Sioux. Our story begins in a modest log cabin on April 6, 1909 where an Indian girl has just given birth to a son, her first born of twelve children. They would name their son Wowacinye that means dependable. It was an honor to be named after his great uncle the famous Sioux warrior Wawacinye who was known to the whites as Martin Charger, and whose father was Turkey Head. Tribal tradition records that Meriwether Lewis while on the great expedition with William Clark and the Corps of Discovery sired Turkey Head. Controlling white society dictated that all Indians have English names. The family Wowacinye had been born into adopted the name Thompson after the grandfathers step uncle, a white man they liked and respected. Wowacinye would be known in the white man’s world as Harry DeSmet Thompson, his middle name displaying the significant respect many Missouri River tribes felt for the famous Jesuit Priest Father DeSmet.

Young Harry learned how to hunt, fish, and trap during those early years on the reservation. He had good times with his brothers, sisters, and friends just being an Indian boy on the banks of the wide Missouri. Harry was a student with promise but schooling was very limited on his reservation.

It was decided that he should attend a high school work study program administered by the American Missionary Association about 160 miles down the Missouri River, across the boarder into Nebraska on the Santee Sioux Reservation. Harry recognized this opportunity as both sweet and sour. The chance for a quality education would be balanced against the separation from his family, friends, and the reservation where his roots are so deeply planted. It would be two years before his first visit back home.

Harry would go to school half a day with the other half set aside for manual labor to earn his way. He mended fences, busted broncos, cut firewood, and did whatever there was. Harry worked as a typesetter on two monthly newspapers printed by the school in the Sioux language, it was here that he learns to read and write in his native language.

Medical services on the Santee Reservation were nearly non-existent and the school had long advertised nationally for a doctor. Doris Sidwell a recent graduate from the University of Vermont Medical College agreed to become their doctor. Ms. Sidwell had met the famous Sioux Indian Charles Eastman in her youth. Eastman, a graduate of both Dartmouth and Harvard, talked extensively on the lecture circuit about the plight and aspirations of American Indians. Doris Sidwell was forever moved by Eastman’s lecture and became increasingly interested in Indian history and culture. The chance to work with and for the Sioux was very much welcomed.

The Santee Reservation was rough and dangerous so the school regularly assigned the older boys to escort Ms. Sidwell as she attended to the sick in remote places. They traveled in a Model A Ford Coupe. Harry was one of Ms. Sidwell’s escorts and a close friendship developed between them. When Harry graduated and took employment in Ohio with a national company specializing in tree surgery, they continued to correspond, occasionally getting together. As these things sometimes go, the friendship turned to romance and blossomed into love. When Doris accepted employment with the Danvers State Hospital in Massachusetts to work as a child Psychologist, Harry transferred within his company to Connecticut. On August 13, 1933 Harry and Doris were married in her mother’s flower garden at Harwinton, Connecticut.

In 1934 and 35 Harry attended the University of Massachusetts at Amherst and took a two year program in Horticulture. Whenever Harry and Doris could fit it in they went to the White Mountains of New Hampshire and camped in a tent. After their two daughters were born they bought a trailer and would do there camping at White Lake State Park.

When World War II came along Harry at age 34 took time off from the family and career to be a warrior. He got the required three letters of recommendation and volunteered for the army’s Elite 10th Mountain Division. He spent eight months in the war zone of Italy; part of a 105 Mule Pack Howitzer gun grew.

Harry had been trapping nearly continuously since he was 12 years old. His first trapline in the Fort Hale district of the Lower Brule reservation produced mostly skunks, but soon he was catching coyote. His early furs were sold to Sears and Robuck, the Burman Brothers in Minneapolis, Minnesota, and E.A. Stevens in Helena Montana.

Harry did his trapping wherever he was, but it was usually part time until he got to Massachusetts. In 1935-40 Harry was a caretaker for a large farm owned by a couple of retired schoolteachers. During the late fall and winter the farm responsibilities declined and the trapline became full time until spring. Harry caught his first red fox in Boxford, Mass; he utilized a dirt hole set as described in a trapping manual by E.J. Dailey.

In the summer of 1950 the Thompson’s bought the Old Gilman Farm on Whittier Road bordering the Bearcamp River. The buildings were dilapidated but structurally sound. Harry saw the agricultural potential in the 23.5 acres and considered it a good base to hunt and trap from. The first fall in 1950 while on the farm in New Hampshire, Harry put out a trapline for all species and has continued to trap every year since.

Harry’s favorite trapping is for beaver through the ice. The most beaver he ever caught was 121 in the early 70’s and the largest was 72 pounds caught in a #21 Blake and Lamb. In the 60’s the Conibear style of trap came out and Harry learned how to use them. These days Harry still takes about 30 beaver per year depending on weather and price.

In 1975 we almost lost Harry when he fell through the ice while trapping beaver by himself. The shovel he was holding keyed across the hole and prevented him from being lost under the ice in water over his head. Harry struggled alone until he was able to flop out on the ice. Despite the cold he finished setting his trap, then headed for the truck on his snow machine. His cloths froze hard and his senses where dulled by hypothermia but he made it. Thinking back, he knows he was lucky. Harry is a lot more cautious on ice now. Besides nearly drowning or freezing to death, Harry also caught himself in a 330 Conibear trap once but luckily had a friend along who could get him out.

When coyote moved into New Hampshire, Harry already knew how to catch them from his experience in South Dakota, the most he ever caught was 13. Harry says, “Bill Hoffman of Manitoba, Canada produced the best coyote lure ever.”

Harry also liked Fisher Trapping and his biggest catch ever was 17, he was a friend with two of the best Fisher trappers in the state; Malcome Locke and Alex Troy. Harry remembers two freak catches. Once he caught two beavers together in a single #14 trap. They must have been swimming side by side over the dam as each had one front foot caught. Another time Harry caught a mink and a muskrat together in a 330 Conibear trap. He figures the mink must have killed the muskrat and then swam into the trap hauling the rat.

For three years in the 80’s Harry hosted a fur auction at his farm in Tamworth, he provided the place, the coffee, and hard liquor. The fur buyers were Al Morgan, Al Morgan Jr. both of Enfield and Bill Birkbeck of Conway. It worked well until the bottom fell out from fur prices. In 1986 there were approximately 800 licensed trappers in New Hampshire about ten of them made over $3,000 per year at trapping, Harry Thompson was one of that small group.

At one time Harry trapped in ten towns over two counties; today he traps only in Tamworth, Ossipee, Sandwich, Albany, and Madison. Harry still uses the same yellow snowmobile he has had since the 60’s and pulls trapping gear over the snow on a wooden sled crafted for him by Ed Moody the man who made the dog sleds for Admiral Bird and went along on the expedition to the South Pole. Besides being a trapper, Harry has been a registered deer and bear guide for 25 years.

Harry Thompson has been written about quite a few times since he started trapping in New Hampshire. When Harry was in his 50’s and 60’s the articles were about his knowledge and skill, in his 70’s and 80’s the writers were amazed at his desire and persistence still trapping hard in a young man’s game.

Doris passed away in August 1994 and Harry now lives alone. The house, barn, and property are all kept neat and organized. At almost 92 years old Harry Thompson looks healthy and strong, he is just under six feet tall and stands up straight, he remembers all the details of his life including dates. Harry is hoping for a January thaw to melt the snow then a good freeze to make the ice thick and safe. Harry has a brand new hand operated ice auger he wants to try this year while spring beaver trapping through the ice. For forty plus years newspaper and magazine articles have recognized the skill, persistence and accomplishments of this trapper, who has kept them in awe. To all of us trappers Harry Thompson is truly a treasure. We worry about Harry trapping alone but would never suggest that he stop. Harry would welcome company on his trapline and the opportunity to pass along his knowledge and skills, just as long as you don’t slow him down to much.

Harry’s classmates at Massachusetts State College called him Tommy and had this to say in their class yearbook.

“Tommy has been a distinct character on our campus, quiet, good-natured, and sociable; he is liked and respected by everyone. Those of us who have listened to his tales of life on the Indian Reservation will always remember him. While with us, he distinguished himself as a ground-gaining football back and the best boxer in school. His chief interest is in trees. May you, like your trees live long, Tommy.”

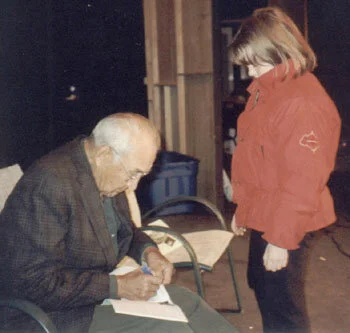

At the February, 2000 directors meeting of the New Hampshire Trappers Association, Harry was nominated for induction into the Trappers Hall of Fame and a unanimous vote of the officers and directors makes Harry Thompson the seventh New Hampshire trapper to be so honored. The presentation of the award was made on September 16 at the fall meeting with the general membership present.