Harris Ilsley

Inducted into the NHTA Hall of Fame in 1998.

The Square Dance Kid: As told by Mel Liston

Our story starts about a hundred years ago in the North Country of New Hampshire. Seems one Lewis Ilsley of Errol was a logger in the winter, often ran a grain thrashing machine in the summer and for a period of time was the road agent for the 13 mile wood section now part of Route 16. The girls were kind of far apart up they’re in the North Country and Lewis got to be 32 years old before he finally snagged one. Down around Plymouth there always has been a healthy supply of unmarried females because of the teachers college and that’s where Lewis met Mildrid. It didn’t take them long to get hitched and start producing a near endless supply of offspring. There would be nine young uns all told sept one didn’t make it at childbirth. They were all girls except for two boys and our story is about the life and times of one of the boys, “Harris” who was the seventh born.

Sometime during the formative years of the expanding Ilsley family they moved to Weare, New Hampshire and established a dairy and cattle operation. Harris was born on August 18, 1930 in the farmhouse at Weare; and he has stayed pretty close to home his whole life.

When I say he has stayed close to home I mean he has been within walking distance of his front door more than 99 percent of his life. Harris can give you details of every excursion he ever made outside the state. Twice as a kid Harris got to go and visit his uncle who lived in Wilson Mills, Maine and maintained the hydroelectric dam at the outlet of Aziscohos Lake. Twice he went to Fenway Park in Boston to watch Ted Williams play ball. Once he went to Rhode Island to deal with some sticky domestic stuff. Once Harris was across the boarder into Canada just to take a look-see the other side and once he ventured into Vermont to do some “hellin” around as Harris puts it.

When Harris was just a little fella the farm operation branched out into laying chickens so the family made it’s living selling milk and eggs, some at the roadside for retail with the bulk of the product picked up once a week by the large wholesalers. Typical of most rural community’s back then, they swapped chores, favors, equipment and generally supported each other in their community by buying and selling each others produce and labor.

One of Harris’s earliest and most enduring memories of this childhood was the hurricane of 1938. The rain was so long and hard that the dams on both the Deering and Weare reservoirs were seriously overflowing when they burst during the morning. The surge that came down the valleys below carried whole factories, houses, barns, farm animals, wildlife, trees and people with it.

Remarkably nearly all the people survived. Harris remembers stories of some old women that were swept away and never found. As kids Harris and his friends were always searching for their bones when they were fishing or trapping along the river. During the storm and flood, three of the houses next to the Ilsley farm washed away. All the auto and railroad bridges were down, the telephone and power lines were mostly down.

The milking parlor was under water and the cows were up to their necks standing in the mud and water bellowing to the milked. The family waded into the mud and water, got a hold of each cow one at a time and led them up onto a nearly knoll where they milked them all out by hand. In the beginning the high water was full of silt and debris. Until the flood reached its crest no one could be sure they would survive, remarkably they all did.

Within a few days it was clear blue sky, the mud and silt had settled in what was now a lake full of islands. To an eight year old boy it was a beautiful and interesting sight to see and Harris has some good memories of their families struggle and that time he had off from school. The Federal government moved in with the WPA and CCC to put services back into order and rebuild some of the infrastructure. I asked Harris, “How long it took to square things away?” Harris contemplated a little then said, “It never has gotten squared away.”

As much as Harris enjoyed his time off from school he had to go back to the little schoolhouse near by, which handled grades 1-6. Grades 7 and 8 went to a larger school in the center part of Weare. Harris hung his books up for good in grade 8, at that time in his life there were a lot more things to do than waste time in school. Harris says, school was poison for me and I just used it for resting anyway.

Harris worked hard on the family farm, as did all the kids. Harris had helped with chores as far back as he can remember, at age five he had his own laying hens and would sell his eggs right along with the family business. One day a fisherman stopped by to get eggs or milk and asked if he could dig some worms in their manure pile. Harris dug the worms and another businesses was off and running. Harris advertised them as mud worms and he kept a good supply on hand. For many years all the fishermen around Weare knew they could always get lively fat worms for bait at the Ilsley farm.

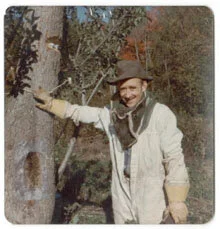

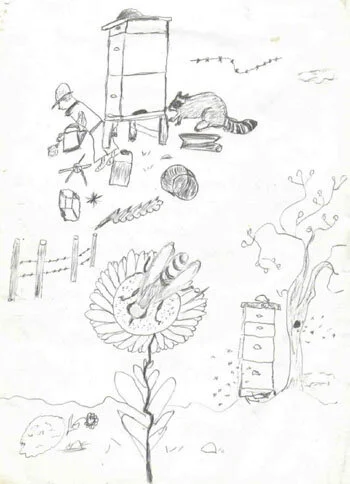

One of Harris’s responsibilities was to keep the vermin under control around the farm; this would include everything from mice to crows. The skunk, foxes and coon were a problem for the chickens so Harris got after them with traps. Harris learned how to skin and care for the pelts on those early critters. Back then Sears and Robuck was not only where you bought everything but also it was were you sold your furs.

So Harris shipped his furs to Sears. When the fur check came back there was a note that he was three reds under and three grays over that is how Harris learned that he was trapping gray fox instead of red fox. Harris liked trapping and did it as much as he could, from about mid 1940 through the 60’s but he was always limited by farm chores and other ventures which seamed to make more dollars and sense. He trapped from a bicycle with a box strapped on back. Harris trapped skunks, coon, fox, mink and muskrat but the hides that had value were muskrat in volume at 80 cents each and mink at 25 to 30 dollars each.

All the Ilsley children worked hard on the family farm people today might say the children were abused but they definitely learn responsibility. Harris did all he could to help out and looked under every rock for a new buck. He dug hundreds of porcupines out of the ledges for the 50-cent bounty paid by the state.

He raised pigeons to sell for pets or meat as squab. He picked up apple drops all over Weare and pressed it into cider. He kept hives of honeybees at various properties around Weare and hunted wild bees for honey. One year Harris harvested over ¾ ton of honey from wild and domestic hives. Responsibility and chores were always there for Harris so he looked at every angle to turn a buck without leaving the farm. In the late 60’s furs were once again in demand and raccoons were worth $25.

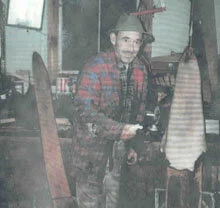

A hard working coon hunter with good dogs could get about 100 coon a year, but he would have to be up late every night hunting and then still skin flesh and stretch the hides which was a lot of additional work. Harris got the local coon hunters to bring the coons to him; he would do all the skinning and fun handling for half the value. It was a win/win deal and he did about 500 coon the first year. Harris wanted to do fur handling for trappers also which was a larger market but trappers generally did there own and would never pay the premium, coon hunters did. So Harris established a fixed price to skin coons at $3 and immediately started skinning about 1,000

Harris took a beating that first year doing twice as many coon and making half as much money but the trappers liked his honesty and skill. Soon the trappers started bringing in all kinds of fur and till this day Harris skins whatever comes in the door. Most of his business is for trappers these days, but some hunters bring animals they want skinned. Generally Harris will skin about 3,000 animals a year and about 1,500 to 2,000 of those are beaver. Harris established his prices for skinning in the 60’s and hasn’t raised them in 40 years.

I asked him about that and Harris said, “Never had any great expectations, just hope the trappers keep the furs coming because, business is based on skill and volume. I get faster every year and would like to challenge the trappers to try and swamp me.”

Harris never married, never even kept a woman, and says he likes them but they never looked good the second time. In his sporting years he was known in surrounding towns as the “Square Dance Kid”, and he danced with three generations of girls but refused to get caught. Harris says he didn’t mess with girls in town because he was doing business with their fathers.

I suspect that Harris has been married all along. He was married to a tough but good life, to a farm with responsibility to crops, animals, and a family which had to stay together to survive, to a lifestyle dictated by the weather, the seasons and the times. Married to a whole lifetime of collecting milk, eggs, apples, firewood, maple sap, wild furs, and porcupines for bounty.

The cows and chickens are long gone, the family has died off or moved away, the buildings will have to stand awhile longer without repair. Harris is still there, married to that piece of ground to those old buildings and what’s in them, to the lifetime of experiences and memories in Weare which must be triggered as he looks toward the valley that was once flooded, the pastures where the cows grazed, the highway out front where the customers stopped to purchase their eggs, milk or fishing bait.

As the Harris of seven decades stands before me, he’s a lively nimble man who chew’s his pipe more than he smokes it, his mind is as clear as a bell and there is a twinkle in his eye. I know that this man is the real McCoy, he was the “Square Dance Kid”. Over his shoulder I notice his collection of finely carved and painted songbirds that go beyond the skill of craft into the realm of art and I know that Harris has done well with anything that opportunity presented.

Harris Ilsley skins more animals in a year than most trappers will do in a lifetime; he does a skillful job that prepares the pelt in a way that enhances its grade. A lot of trappers take their furs to Harris for the quality workmanship at a fair price and for the chance to visit with this unique individual. Harris is a member of the New Hampshire Trappers Association and has long been held in the highest regard by its members and all trappers who know him. In the year 2000 Harris Ilsley was recognized by his fellow trappers and shown their highest honor by being inducted into the “The New Hampshire Trappers Hall of Fame.”

Harris Ilsley passed away on September 26, 2019 at the age of 89, after a brief illness. His quick wit and ability to strike up a chat with any wanderer inside his fur shop will be greatly missed throughout New Hampshire’s robust hunting and trapping community.