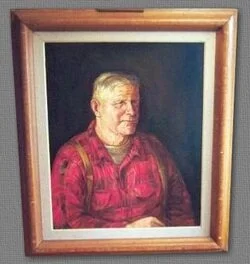

G Malcolm Locke

Inducted into the NHTA Hall of Fame in 1999.

No other trapper from the state of New Hampshire gained as much recognition around the state, nationally and to some extent internationally as G. Malcolm Locke of Barnstead.

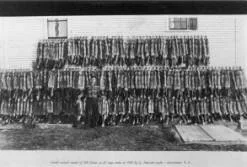

Malcolm’s international notoriety comes as a result of his catch of 200 foxes in 26 days in 1945, a story which was picked up by the Associated Press and printed all over the world.

Women from all over Europe saw the picture of the rugged young trapper with all those foxes and started to do their calculating. Based on the cost of a fur coat in their war-ravaged economics, they figured Malcolm must be a millionaire.

Letters started coming to Malcolm from Belgian, French, and English women who made various proposals the least of which was marriage.

This must have made the small town country farmer and trapper blush. I am informed by a reliable source that his wife, Elva, took it all in stride. Malcolm got around $1400 for his fox catch which was a nice piece of change for a months trapping in 1945.

Back in those days, much more than today, trapping was a secretive thing. Few trappers let on to how many furbearers they were catching. Trappers didn’t talk much about their methods, lure recipes were guarded like secret formulas for rocket fuel and anyone you met on your trapline was considered a possible spy, thief, claim jumper or other suspicious type.

Most trappers would prefer you didn’t know who they were or what they were doing. Malcolm on the other hand was outspoken and gregarious, he felt confident that no other trapper had done what he had and so he declared his catch to be a world record. As time passed his record was accepted since no trapper came forward to refute it. Malcolm wrote his first of three trapping manuals entitled, “The Details of Fox Trapping” in 1946.

Unlike most trappers Malcolm would publicly share his knowledge, techniques and perceptions about fox trapping in his manual which would allow him to further capitalize on his world record catch and establish himself as a trapper of national standing. That first big catch with the manual it produced, a long trapping career with other big catches and two additional manuals in later years, have assured Malcolm a level of national fame and a place in trapping history for as long as trappers can read.

Here in New Hampshire the trapping accomplishments of Malcolm Locke are well known and the closer you get to Barnstead the more his fame is legendary. Local people knew Malcolm as more than the famous trapper, he was a carpenter, a town cop, a serious hunter and fisherman, a fine farmer who specialized in strawberries and corn, a generally well known and liked character.

Malcolm’s son John says that for many years they kept between forty and fifty hounds to run fox, bobcat, and raccoon. John remembers one blue tick hound named Ole Blue, which was their best ever, coonhound. Problem with Ole Blue was that he wouldn’t leave the skunks and porcupine alone so he was always sick or stinky. The most successful line of coon and cat hounds they ever produced came by accident when the best Treeing Walker bitch got loose and bred with the neighbors chow.

Those dogs would run silent on air scent until they closed on the quarry then would open up just before the tree. They were rugged fight dogs and a lot of hounds’ men bought that line. Many local and seasonal folks knew Malcolm as the farmer who along with his grandson Nathan operated a large pick your own strawberry business along with sweet corn sold at the stand. Malcolm hunted deer with local people and had trapping partners later in life, he crossed a lot of people’s path and they all have their memories.

This author traps a small portion of what used to be Malcolm’s territory and all the landowners that go back that far remember him well. The continuing presence of Malcolm on my trapline plays out in different ways. Sometimes the landowner will verify that my traps are in the right place, cause that’s where Malcolm used to set his. Other times it will be an endearing story from a landowner that appreciated knowing Malcolm. Fred Goodrich of Barnstead remembers well when Malcolm first came to ask permission of his father to trap on what was then the family’s summer home and is now Fred’s residence.

Malcolm was the local one-man part time Police Chief. Fred’s father was vacillating as to whether he would give Malcolm permission to trap and Malcolm said, “well you know if you give me permission to trap out here I guess I can keep a pretty good eye on things while you’re gone for the winter, but if you don’t then I guess I won’t have much reason to be out this way.” That was how Malcolm added the Goodrich property to what was a very extensive trapline. Malcolm’s trapline was one of his most prized and protected possessions. Malcolm stated his personal attitude on this matter in his first trapping manual when on page seven he writes;

“In establishing your trap-line you may be getting a little competition, for some of your sets are bound to be seen and copied by others; this may not bother you too much, but in the first few years of your trapping, build up a good trap-line and hang on to it.”

Malcolm would hang on to his trapline as best he could even after his age and health would no longer allow him to utilize it. In his youth Malcolm would trap alone but in later years would take on partners who could learn from him and do the heavy lifting, but no one was ever allowed to trap his territory without him being involved. Backing down from his extensive trapline territory first a little and then a lot must have been an awkward and difficult process for Malcolm. Malcolms trapping partner for the last ten years that he remained active was John Abbott of Barnstead and Malcolm relinquished his territory to John.

Malcolm expressed his good fortune that he lived where he did, when he did, that he was able to have the life, which was his. Without a doubt, Malcolm was in the right place at the right time with the right stuff. When Malcolm started trapping at nine years old in 1913 the state of New Hampshire was ninety percent cleared with forests being mostly along the edges of fields or following a gully on river bottom.

The environment for small game was fantastic. Rabbits and partridge were thick and mice and squirrels were everywhere around crops, fields, and orchards. Fox were thick in this environment. When World War II came around our government decided that farmers in the Northeast should raise the bulk of the chickens and eggs for the war effort. Large-scale chicken farms were everywhere; the farmers generally threw out the broken eggs and dead chickens with the hen manure.

Foxes were attracted to this new food supply and multiplied as a result of the year round supply of reliable feed. Malcolm had already attained his trapping skill when in 1945 the fox population was peaking in New Hampshire, the price for fox pelts was rising and he was available with sufficient equipment, territory, stamina and knowledge to go after them aggressively. Malcolm saw a window of opportunity and he went through it during the short period it was open. Malcolm made his record fox catch just before the fox population began its decline.

In the early fifties the government no longer encouraged the chicken industry exclusively to the Northeast and the railroads were allowed to raise freight charges on grain shipped in from the West. The industry was in a long decline and disappeared completely by the sixties along with the unnaturally abundant food supply for the fox. Malcolm mentions poultry farms several times in his fox-trapping manual, and one of his highlighted sets was a hen manure pile set.

Malcolm would continue trapping through the years and would be presented with another trapping window of opportunity in the mid-sixties. The movement away from farming had allowed the forest growth to come back in the less utilized native pastures so that the state was then about 70-80 percent forested. Small game such as partridge and rabbits were on rapid decline due to change in habitat and a renewed predator on the scene was ravaging what was left. The fisher had retreated north to the few remaining forests staying ahead of the land clearing for agricultural use started by the first European settlers.

By the early 1900’s fisher where nearly eliminated from New Hampshire and much of the United States because of over harvesting and poor forestry practices. The New Hampshire fisher-trapping season was closed from 1934 until 1961 when it opened for one month in Rockingham and Strafford counties and twenty were taken. The fisher population was exploding and by 1966 there was a three-month season with no limit on catch. Malcolm had been catching quite a number of fisher each year in his fox sets, which he would let go. The first year he could legally trap fisher he took thirty but by 1966-67 he knew how to catch them and took 206 during the three-month season. The total catch for the state was 407 that year.

Malcolm had knocked the population down in his area, which prevented a repeat performance for him in the following years. Malcolm authored his second trapping manual in 1970 titled, “Trapping Tree Climbing Animals” which was primarily a fisher trapping manual. By 1971 the state fisher take had maxed out at 1130 and by 1974 with a lot more trappers after fisher the take was down to 456. The season was closed in 1977 and reopened for two weeks in 1979. Since then Fish and Game has manipulated the season length and limit more closely to manage the population. Presently the season is the month of December, with a limit of ten fisher throughout most of Malcolm’s old territory.

Malcolm really did shine with record fox and fisher catches but beyond that he was an all around trapper, he especially enjoyed beaver and otter trapping and wrote his third and final trapping manual in 1972 which he entitled, “The Trapping of Beaver and Otter Talk.”

Malcolm never made much money from his trapping manuals because he couldn’t merchandise them properly. Eventually Malcolm sold the exclusive rights to his trapping manuals for $10,000 to Pete Richard another famous trapper, lure maker, and equipment supplier.

Malcolm’s wife Elva had passed away in 1996 and now he would finish the last decade of his life in a nursing home visited often by a large group of faithful friends and a family which includes two children and seven grand children. Malcolm’s memories would give him comfort until his death in the spring of 2000.

Malcolm was a member and past president of the New Hampshire Trappers Association, many of our older members were his friends. Eighty-eight year old Alex Troy of Ossippee use to supply Malcolm with anthill dirt for his fox sets in exchange for strawberry preserves. It would be a rare trapper in New Hampshire who hasn’t read one or all of Malcolm’s trapping manuals. At the February directors meeting of the New Hampshire Trappers Association, Malcolm was nominated for induction into the Trappers Hall of Fame. The presentation of award will be made posthumously on September 16 at the fall meeting with the general membership present.